Data Compliance: Build a Program That Actually Works

Most organisations don’t fail at data compliance because they “don’t care.” They fail because compliance gets treated like a one-time project (write policies, update a notice, run a training, tick a box) instead of a living program with owners, controls, evidence, and continuous improvement.

A data compliance program that actually works is one that:

Reduces risk in day-to-day operations (not just in documents)

Produces reliable evidence when regulators, customers, or partners ask

Survives staff turnover, vendor changes, cloud migrations, and new products

Aligns privacy, security, records management, and governance into one operating rhythm

For Jamaican organisations navigating the Data Protection Act (and often sector expectations, contractual requirements, and cyber risk), this shift from “paper compliance” to “operational compliance” is the difference between being compliant on a slide deck and being compliant in reality.

Define what “data compliance” means for your organisation (before you build)

Data compliance is not one law and not one department. It is the practical ability to meet your legal and contractual obligations for personal data (and, ideally, all sensitive business data) across how you collect, use, share, store, and dispose of it.

In Jamaica, that frequently starts with the Data Protection Act obligations, but the real-world scope often includes:

Customer and employee privacy expectations

Vendor and outsourcing requirements (especially where overseas cloud services are involved)

Cyber security controls and incident readiness

Records retention and defensible disposal

Board and management accountability (governance)

If your program is unclear about scope, it will either become too big to execute or too narrow to protect the organisation.

Practical tip: Write a one-page “data compliance charter” with three items only: what data is in scope, which entities/business units are in scope, and what outcomes you will measure.

Start with outcomes and risk, not documents

A common misstep is starting with a policy library. Policies matter, but they are outputs. Programs work when they are built from outcomes and risks.

A simple way to structure this is:

Outcome 1: You know what personal data you have and why (inventory and lawful processing)

Outcome 2: You can meet rights and transparency expectations (notices, requests handling)

Outcome 3: You control sharing and third parties (vendor governance)

Outcome 4: You can prevent, detect, and respond to incidents (security and breach readiness)

Outcome 5: You can prove it (evidence, metrics, audits)

This approach also helps leadership understand the program as operational risk management, not just legal overhead.

If you need a Jamaica-specific starting point on obligations and terminology, see PLMC’s guide: Jamaica Data Protection Act Explained for Businesses.

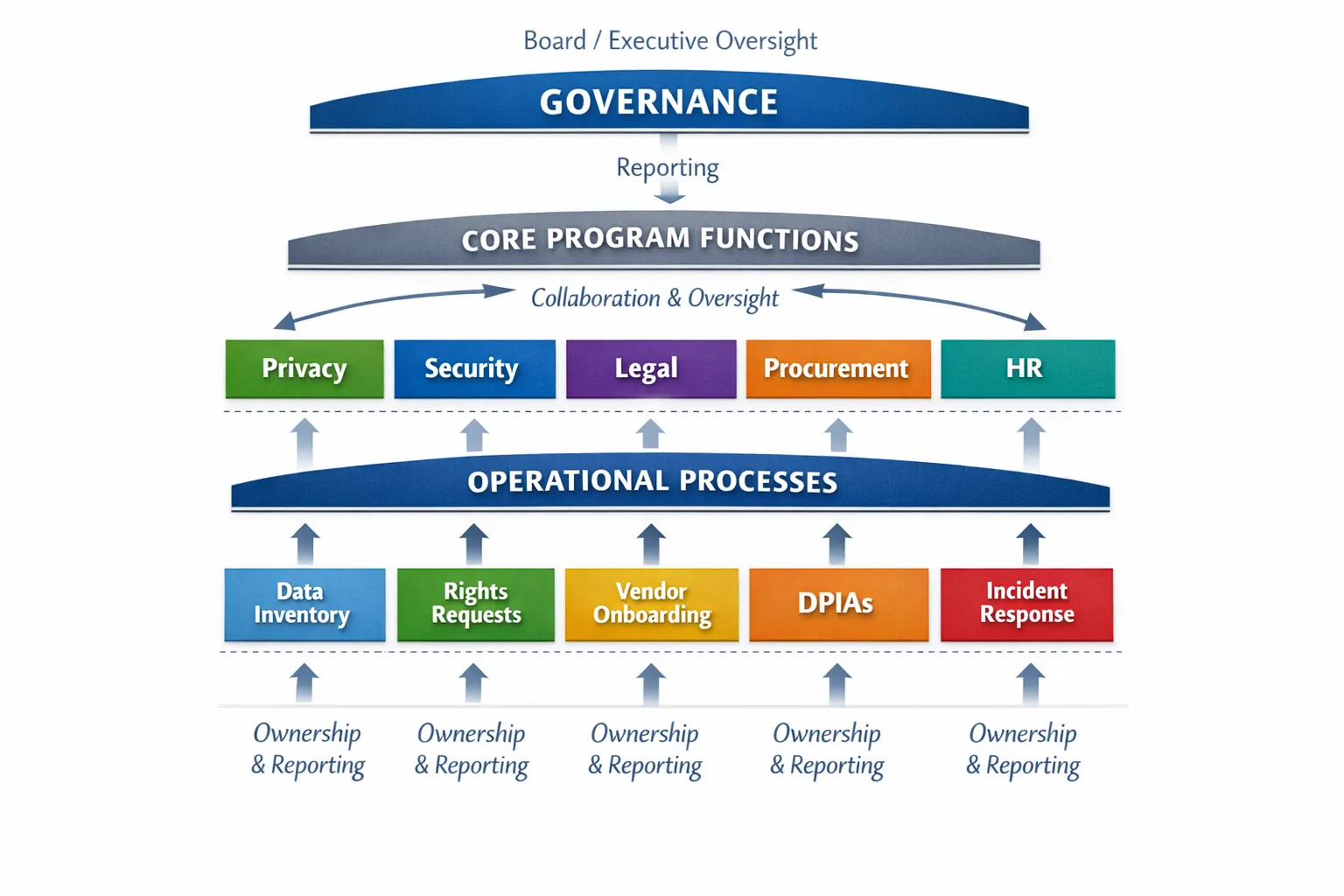

Build the operating model (ownership is the real compliance control)

If nobody owns a process, it will not run consistently. A working program assigns ownership, defines handoffs, and creates escalation routes.

At minimum, most organisations need clarity on:

Board/Executive oversight: sets risk appetite, receives reporting, approves resourcing

Program lead (privacy/compliance): maintains the framework, coordinates evidence, drives improvements

IT and cyber security: implements technical controls, logging, access, incident response

Legal/HR/Operations: controls collection points, employee data practices, contracts, discipline

Procurement/Vendor management: enforces onboarding and contract controls

Business unit owners: accountable for the data they use and the processes they run

A simple RACI to prevent “everybody thought somebody else did it”

Use a RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) to make execution predictable.

Program activity | Accountable | Responsible | Consulted | Informed |

Data inventory and data flow mapping | Business unit head | Privacy lead + process owners | IT, Security | Executive sponsor |

Privacy notices and transparency updates | Legal/Privacy lead | Marketing/HR/Operations (as applicable) | Security, IT | Executive sponsor |

Rights requests (access, correction, deletion, objection) | Privacy lead | Operations/Customer service + IT | Legal, Security | Executive sponsor |

Vendor onboarding and data processing agreements | Procurement lead | Procurement + Legal | Privacy lead, Security | Business owner |

DPIAs (high-risk processing assessments) | Privacy lead | Project manager + business owner | Security, Legal, IT | Executive sponsor |

Incident response and breach handling | Security lead | Security + IT + Privacy lead | Legal, Comms, HR | Executive sponsor |

Training and awareness | HR/Privacy lead | HR + Privacy lead | Security | All staff |

You can scale this model for SMEs by combining roles, but you should not skip the clarity.

Treat your data inventory as program infrastructure (not a one-off spreadsheet)

You cannot control what you cannot describe. A data inventory (and supporting data flow understanding) becomes the backbone of everything else:

Privacy notices become easier to keep accurate

Vendor risk reviews become faster and more consistent

Retention decisions become defensible

Incident response becomes less chaotic

DPIAs become grounded in facts

A strong inventory does not need to be perfect to be useful, but it must be maintained. That means defining triggers for updates, such as:

New system implementation

New vendor or outsourcing change

New customer channel (mobile app, WhatsApp ordering, online forms)

New analytics/marketing tooling

New data sharing arrangement

If you want a ready-to-use set of evidence items many Jamaican organisations build toward, PLMC’s Privacy and Data Protection: A Practical Checklist is a good reference point. Use it as an evidence target, then operationalise each item into a process.

Convert legal principles into repeatable business processes

A program works when legal expectations become “how we do things here.” This is where many organisations struggle, because they stop at policy statements.

Instead, define a small set of core processes with:

A named owner

A standard workflow

Required inputs/outputs

A record of execution (evidence)

Below are the processes that typically create the biggest compliance impact.

1) Rights requests workflow (make it boring and consistent)

Your rights process should be designed for real life, meaning:

Clear intake channels (webform, email, in-person, customer service)

Identity verification rules that match risk

A triage step (what right is being requested, what systems are involved)

A repeatable IT retrieval method (so it does not become an ad-hoc scramble)

A response template and sign-off process

The goal is not just to “answer requests,” but to answer them consistently and with an audit trail.

2) Vendor and outsourcing controls (where risk quietly multiplies)

Data compliance fails in vendor relationships when procurement focuses only on cost and delivery. Build a minimum privacy and security gate into vendor onboarding.

That gate typically checks:

What data the vendor will access and why

Where the data will be stored/processed (including cross-border considerations)

Security measures and incident notification expectations

Sub-processor use (if any)

Contract clauses (processing instructions, confidentiality, retention, assistance with rights, breach support)

If your organisation uses multiple vendors, this one process often delivers disproportionate risk reduction.

3) Retention and disposal (compliance is also what you delete)

Many organisations keep personal data “just in case.” That creates unnecessary exposure in breaches, litigation, and internal misuse.

Build retention into operations by:

Defining retention rules by record type (HR, customer accounts, CCTV, marketing leads)

Connecting retention to systems (automated deletion where possible)

Creating a defensible disposal log or mechanism

Retention is also a governance conversation, not just a privacy one, because it touches audit, finance, HR, and operational continuity.

4) Incident readiness (test it like you mean it)

Having an incident response plan is not the same as being incident-ready.

To operationalise incident readiness:

Run tabletop exercises with privacy, security, IT, legal, and communications

Define what must be logged during an incident (timeline, decisions, notifications)

Create a breach triage method (what happened, what data, how many people, likely impact)

This is where privacy and cyber security must work as one system.

5) Privacy by design (so projects stop creating new compliance debt)

If privacy is only reviewed after launch, you will permanently chase gaps.

Embed privacy in change management by introducing simple triggers, for example:

New processing of sensitive categories of data

New monitoring or profiling activities

New data sharing with third parties

New technologies that materially change risk (biometrics, AI features, large-scale CCTV analytics)

A lightweight DPIA approach is often enough for most projects, as long as it is used consistently.

Design your evidence system as you design your controls

When regulators, customers, banks, or partners ask “show me,” you should not rely on memory or a last-minute scramble.

A practical way to avoid this is to decide, upfront, what evidence each control produces.

Control area | Process evidence (examples) | Why it matters |

Data inventory | System register, data flow notes, processing purposes, owners | Proves awareness and supports transparency |

Rights handling | Intake logs, identity checks, response templates, completion records | Demonstrates repeatability and accountability |

Vendor governance | Due diligence records, signed agreements, security questionnaires | Shows you control third-party risk |

Retention | Retention schedule, deletion logs, archival rules | Reduces exposure and supports defensibility |

Training | Attendance records, role-based materials, refresh cadence | Proves awareness and supports culture |

Incidents | Incident logs, tabletop exercise reports, corrective actions | Shows readiness and continuous improvement |

The best evidence is created as a by-product of normal operations.

Measure what matters (and report it like a risk program)

A working data compliance program has metrics that leadership can understand and act on. Avoid vanity metrics like “we have a policy.” Track performance and risk.

Use a mix of leading and lagging indicators.

Metric type | Example metrics | What it tells you |

Leading indicators | Percent of key systems inventoried, percent of critical vendors assessed, training completion for high-risk roles, number of DPIAs completed for qualifying projects | Whether controls are being adopted |

Operational performance | Average time to complete rights requests, number of overdue requests, time to approve vendor onboarding, time to remediate high-risk findings | Whether the program runs smoothly |

Lagging indicators | Security incidents involving personal data, repeat audit findings, policy exceptions, customer complaints related to privacy | Where risk is materialising |

For many Jamaican organisations, quarterly reporting is a realistic cadence to start, with a short dashboard that ties metrics to risks and remediation.

If you want a time-based structure for the year, PLMC’s Data Protection Jamaica: Compliance Roadmap for 2026 provides a helpful quarterly rhythm. Even if you adapt the dates, the sequencing (governance, inventory, operations, testing, improvement) is sound.

Why most data compliance programs fail (and how to fix the pattern)

Programs usually break in predictable places.

They become “legal only” programs

If privacy sits entirely with legal, it often lacks technical enforcement and operational traction. Fix this by co-owning the program with security, IT, procurement, and business units, using clear RACI and measurable controls.

They rely on training without process

Awareness is important, but staff cannot “train their way out” of unclear workflows. Fix this by defining standard operating procedures for the few processes that create most of the risk (rights, vendors, incidents, retention).

They treat the inventory as a one-time deliverable

The inventory becomes stale, then everything built on it degrades. Fix this by assigning owners and creating update triggers tied to change management.

They collect documents but not evidence of execution

A policy without execution records is weak proof. Fix this by designing evidence generation into workflows (logs, templates, checklists embedded in tooling).

They do not test incident response

Most organisations find gaps only during real incidents. Fix this by running tabletop exercises and tracking corrective actions.

A practical 90-day build plan (focused on operational traction)

If you are building or rebuilding your program, 90 days is enough time to make it real, even if you do not complete everything.

Timeline | Focus | What “done” looks like |

Days 1 to 30 | Governance and scope | Program charter, executive sponsor, RACI, defined in-scope systems and business units, baseline risk view |

Days 31 to 60 | Core operational processes | Rights request workflow live, vendor onboarding gate defined, incident coordination clarified, first version inventory started |

Days 61 to 90 | Evidence and measurement | Evidence pack defined, initial metrics dashboard, training plan for high-risk roles, remediation backlog with owners and dates |

This plan is intentionally practical: it prioritises ownership, workflows, and proof over perfection.

Align your program to recognised frameworks (without overcomplicating it)

Frameworks can accelerate design and improve credibility with stakeholders, especially if you operate internationally.

Two widely used references are:

The NIST Privacy Framework, which helps structure privacy capabilities in operational terms

ISO standards such as ISO/IEC 27701 (privacy information management), which can be useful if you are aligning privacy with ISO-style management systems

You do not need certification to benefit from the structure. Use them as design guidance, then tailor to your size and risk profile.

When to bring in outside support

Many organisations can draft policies internally. The harder part is building a program that holds up under pressure: vendor issues, incidents, customer complaints, audits, and rapid operational change.

You may benefit from external support when you need:

A practical implementation plan that fits your operations in Jamaica

Independent assessment of gaps and priorities

Role-based training that moves beyond generic awareness

Integration of privacy with governance, risk, and compliance activities

Privacy & Legal Management Consultants Ltd. (PLMC) supports Jamaican organisations with data protection implementation, GRC integration, cyber security services, training, and risk assessment tools. If your goal is a program that can be executed and evidenced (not just documented), you can start with a conversation and map the fastest path from today’s reality to an operational compliance program: Privacy & Legal Management Consultants Ltd.